STAND BY FOR LIFT OFF (Published in Issue 20 of The Football Pink)

- Peter Kenny Jones

- May 14, 2018

- 8 min read

Updated: Feb 18, 2021

THE FIRST WORLD CUP IN ASIA - HELD IN JAPAN AND SOUTH KOREA IN 2002 - WAS SUPPOSED TO KICKSTART THE CONTINENT'S PUSH TOWARDS EMULATING THE SUCCESS OF EUROPEAN AND SOUTH AMERICAN NATIONS. WHILE FOOTBALL HAS EXPLODED AS A SPECTATOR SPORT, ARE WE ANY NEARER SEEING AN ASIAN TEAM CHALLENGE FOR THE CROWN? PETER KENNY JONES LOOKS CLOSER.

The 17th World Cup was jointly hosted by South Korea and Japan. It was a tournament of firsts; the first co-hosted competition; first to use the golden goal rule and the first to be held in Asia. The tournament placed Asian football on the world stage and they more than surpassed their expectations. Japan and South Korea were both defeated by Turkey, Japan being eliminated in the Round of 16, South Korea losing the third-place play-off. It was the South Korea team that most captured the imagination.

Coming top of a group that featured Figo’s Portugal, South Korea went on to defeat an Italian side that included the likes of Buffon, Maldini, Vieri, Del Piero and Totti (who was subsequently sent off), with an Ahn Jung-Hwan golden goal. In the quarter-final the Taeguk Warriors faced Spain; Fernando Morientes had a goal disallowed and South Korea went on to win on penalties. Their semi-final opponents were Germany, a tight game was settled by Michael Ballack who followed in after his own shot was parried by the Korean goalkeeper, Lee Woon-Jae.

South Korea were more than just national heroes, they had delivered the lightning bolt the competition organisers had hoped for. The 2002 World Cup was meant to be the springboard for Asia to become a force in world football. However, since that tournament there has still yet to be another Asian success story. Germany 2006’s best performing team was South Korea again who came third in the group stages, with Iran, Japan and Saudi Arabia all coming bottom of their group. South Africa 2010 saw North Korea and Australia eliminated in the group stages, South Korea and Japan made it to the knockout round but were dumped out by Uruguay and Paraguay respectively in the Round of 16. Despite this improvement in performance, Brazil 2014 again saw all four teams – Japan, South Korea, Iran and Australia – eliminated in the group stages. Heading into Russia 2018, there are five teams faced with the task of representing Asian football and proving that South Korea’s 2002 performance was not a one off. Australia, Iran, Japan, Saudi Arabia and South Korea have the hopes of Asia thrust upon them, sixteen years on from what was meant to be a turning point for the continent’s teams.

So why have Asian teams failed to capitalise on the South Korean success of 2002? Since then there has been a wait for the sleeping giants to awaken in places like China, Japan and Korea on a truly global scale. It appears that the legacy left by the only Asian World Cup to date has not occurred on the pitch. Rather, it has switched the continent on to viewing European and South American football as spectators and speculators rather than as participants. Of course, we’ve seen massive investment in the Chinese Super League, which has attracted the likes of Ramires, Axel Witsel, Oscar, Hulk and Ezequiel Lavezzi; although this has drawn harsh criticism from around the world. Are they there to further the goals of Chinese football or are they foreign mercenaries seemingly leaving behind higher levels of competition for an easy pay cheque and the opportunity to bail out quickly when things don’t go according to plan? Whether this preconception is true or not, it has increased the interest in Asian football – even if it is in the form of naked scepticism.

It is not only the Chinese Super League that is attracting the big names to Asia. The Indian Super League (ISL) has been viewed as a retirement home for some greats of the game. The ISL’s marquee player rule permits each team to sign one star player for the season: Luis García was the first to be signed in this role in 2014 and since then the league has attracted names such as Roberto Carlos, David Trezeguet, Robert Pirès and Alessandro Del Piero. The stark difference between the Indian and Chinese leagues is the age of the star names appearing – the players joining Chinese teams are in the prime of their careers whereas the ISL players that are being attracted are in their late 30s.

Of course, the reasoning behind these leagues allowing their teams to spend such astronomical amounts of money on players is to garner more attention to themselves; and it’s worked. The Chinese Super League has been shown on Sky Sports, illustrating its growing global impact. The hope must be that when Chinese and Indian players are playing with phenomenally gifted individuals, this will then improve their game and those standards will diffuse across their entire football system. By attracting more attention and interest, more money can be pumped into nurturing home-grown talents, thus improving the respective national teams. These nations are viewed as the biggest hopes for the future of Asian football. India has a lot of promise as they attract large crowds – around 20,000 fans each game – which coupled with India’s successful hosting and decent showing in the 2017 Under-17 World Cup (which England won) shows that reasonable progress is being made. However, that reliance on imported and aging talent can only eventually lead to the stifling of their own players over time. With neither India or China competing in Russia this summer, the trickle-down effect has been proven unsuccessful to date.

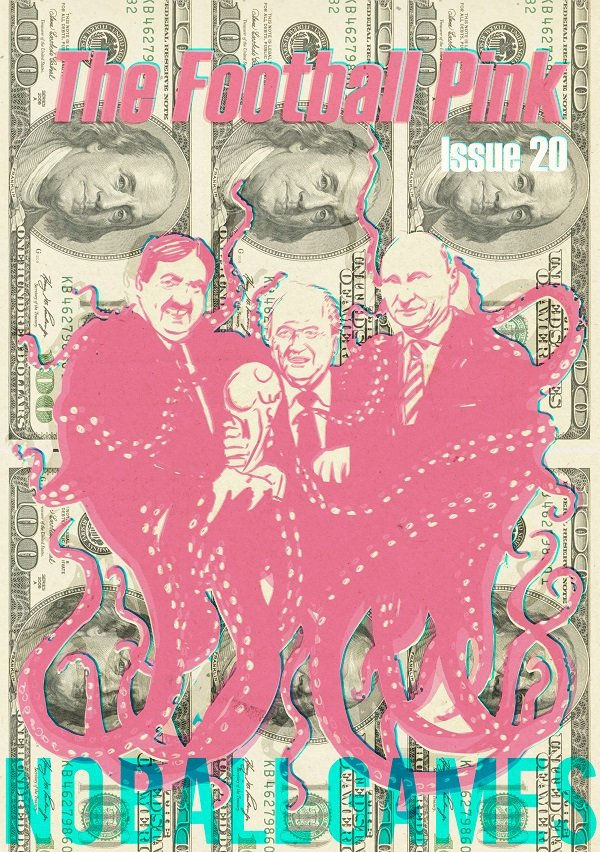

It’s fair to argue that the one of FIFA’s primary aims of awarding of the 2002 World Cup to South Korea and Japan was to get the planet’s most populated continent more interested in playing football as well as watching from the stands or on TV. Asia is a potential goldmine that has yet to be fully utilised; in 2002 FIFA attempted to do so. Six times more people live in Asia than in Europe so the possibility of getting more of them switched on to football would only benefit its governing bodies. It is easy to see the benefits for FIFA and European football by awarding an Asian nation the World Cup and it is an easy argument to present. Since 2002, technology has advanced unabated, giving us all fingertip access to the game all around the world, 24/7, but for Asia the awarding of hosting rights for 2002 was about creating the spark at a more local level. Turning people on to football in their own back yard (almost literally) before they turned on (their TVs) to watch it beamed into their living rooms from thousands of miles away.

Asian football, it’s fair to say, is still streets behind that of Europe and South America and a lot of this is down to the absence of Asian teams in the first organised World Cup tournaments. The first Asian participant was the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) in 1938 but they were making up the numbers for teams boycotting and involved in wars. It’s only been since the 1978 World Cup that there has been a consistent qualification slot for Asian teams, which is only half of all the World Cup tournaments in history. This lack of experience and involvement will no doubt have stunted the progression of Asian sides. The lack of respect shown to Asian teams, who had as much involvement in the spread of football as anywhere else, was narrow minded as the tournament organisers overlooked the integrity of the continent’s teams.

The two most consistent Asian sides in World Cup terms are Japan and South Korea and to fully analyse whether there has been a failure to exploit 2002 must be through the prism of their success in comparison to the other Asian nations. Japan’s J League began in the 1990s although they have had a professional league since the 1920s, so football was nothing new for them in 2002. They were well established and there were many Japanese players scattered across the world, especially those playing in Germany in the 1970s. As for South Korea, their K League has existed since the 1980s and their relationship with football stretches further back even than Japan’s. However, in South Korea football is not the most popular sport and remains in the shadow of baseball. Therefore, the legacy of 2002 was better felt in Japan as the new J League was given an extra lift after the competition.

This meant that the Japanese were able to capitalise better on the impetus given by the 2002 World Cup; the J League was not so dependent on overseas players to attract interest; they were producing great talent of their own. Japanese youth systems are often praised for the coaching of their 8 to 13-year-olds, meaning the production line of technically skilled, good quality players for J League sides – and eventual export to Europe – is fruitful. There are 51 Japanese players playing in England, Spain and Germany alone and this illustrates that Japan is certainly doing something right. Again, in stark contrast to the Indian and Chinese models. The success of technical coaching for Japanese players can be compared to the success of Iran in futsal: they earned a third-place finish in the 2016 Futsal World Cup. It can be no coincidence then that the Iranians qualified so comfortably for this summer’s World Cup.

While the global profile of Asia’s best players has increased over time, the same cannot be said of its coaches. Japan recently appointed Akira Nishino, two months before the beginning of the World Cup. He is just their second Japanese manager in the last eight permanent appointments. This is a trend that is hampering the progression of all Asian managers. Of the five Asian teams to qualify for this World Cup, only Japan and South Korea have Asian managers.

2002 may seem like the dim and distant past but sixteen years is not a phenomenally long time to breed better players, coaches and philosophies which in turn translates into better results. Asia is so vast that it is impossible that every individual nation could improve from the 2002 World Cup to take a place in the upper echelons of FIFA’s rankings, but the growth of the Indian and Chinese leagues highlights a growing interest in the popularity of the game as a spectator sport, while the success of Japanese and South Korean players in Europe illustrates that things are slowly improving in terms of participation and standards. The hope must be that when the likes of Shinji Kagawa and Son Heung-min eventually retire, they can transfer their Champions League and international experience into coaching careers and inspire those that come after them. It is now the aim to continue this growth so that by the time the World Cup comes back to Asia – after Qatar 2022 – its teams can reasonably be expected to challenge for glory.

Although Qatar 2022 has been mired in controversy, having another World Cup in Asia does demonstrate the healthy relationship between football and Asia. So, while football – predominately foreign – has grown exponentially across the continent as an entertainment product since the 2002 World Cup in Japan and South Korea, hopefully by the time it’s ready to play host again, they will have produced at least one team that has been able to stand up to the dominance of the Europeans and South Americans.

PETER KENNY JONES - @PeterKennyJones https://peterkj.wixsite.com/football-historian

*Special thanks to Vikas Sadiq from the Zesh Rehman Foundation and Scott McIntyre, football journalist in Tokyo/Asia.

#TheFootballPink #2002 #2002WorldCup #2002WorldCupKoreaJapan #SouthKorea #Japan #Asia #AsianFootball #Turkey #LuisFigo #Portugal #Italy #GianluigiBuffon #PaoloMaldini #ChristianVieri #FrancescoTotti #AhnJungHwan #TaegukWarriors #Spain #FernandoMorientes #Germany #MichaelBallack #LeeWoonJae #Iran #SaudiArabia #NorthKorea #Uruguay #Paraguay #Australia #ChineseSuperLeague #Ramires #AxelWitsel #Oscar #Hulk #EzequielLavezzi #IndianSuperLeague #LuisGarcia #RobertoCarlos #DavidTrezeguet #RobertPirès #AlessandroDelPiero #DutchEastIndies #Indonesia #JLeague #KLeague #FutsalWorldCup #AkiraNishino #ShinjiKagawa #SonHeungmin

Comments